Definition Time: The Old-Age Dependency Ratio and its Relationship to Insolvency - AMAC Foundation

Perhaps the most significant story relating to the U.S. Social Security system these days is the onerous projection of its looming insolvency. Who hasn’t seen the headlines proclaiming Social Security’s impending “bankruptcy” or the incessant warnings of a major benefit cut in just a few years? As most who are following this unfolding story are aware, the root of the problem lies in the steadily evaporating trust fund reserves that have allowed the program to operate in deficit mode since 2021.

A Snapshot of the Problem

Social Security’s combined trust fund balances at the end of 2020 totaled just over $2.9 trillion — reserves that had accumulated over nearly four decades. Then, in 2021, the program reached a point where total incoming revenue was less than the cost of operating the system, marking the beginning of what is projected to be a steady drawdown of these financial reserves. When the trust fund reserves are fully depleted, Social Security benefits will be forced to move to a cash basis, where benefits paid must equal revenues received. The reality of this situation puts program beneficiaries at risk of severe consequences in just a few years. This shift to cash-in/cash-out is projected to result in a substantial across-the-board cut in benefits that will grow as more retirees enter the program.

Why is this Happening?

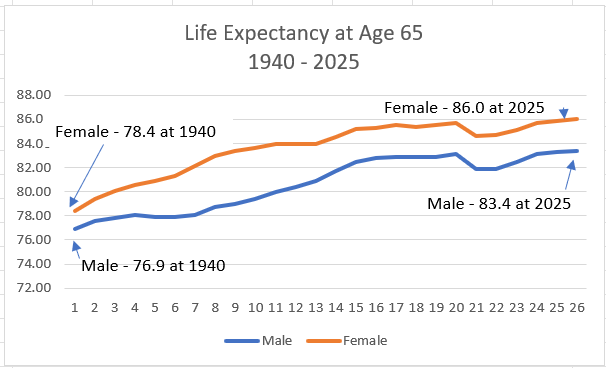

Depletion of Social Security’s trust fund cash reserves can be attributed to several key factors, beginning with the length of time benefits need to be paid to a growing number of beneficiaries. For example, since 1940 life expectancy for those reaching age 65 has grown substantially, increasing by 9.7% for females and 8.5% for males, a trend expected to continue increasing through the end of the century.

Figure 5 – 2025 Social Security Trustees Report, Table VA4. https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/tr/2025/V_A_demo.html#226697

The fact that American seniors are living longer is indeed a positive societal development, but it presents a challenge to ensuring long-term Social Security solvency. When coupled with another key reason for the insolvency problem — the steadily decreasing taxpayer-to-beneficiary ratio — a clear perspective on the demographic challenges facing Social Security emerges. This ratio has steadily declined from 42:1 in 1945 to 2.7:1 today, with projections indicating continued decline in the years ahead.1

The Old-Age Dependency Ratio

Researchers working to address Social Security’s viability as a retirement support system often point to America’s aging population, using a metric called the Old-Age Dependency Ratio (OADR). This metric compares the share of the population aged 65+ with the share of working-age individuals (15-64), providing a picture of the social service, pension, and health care burden that needs to be addressed to sustain a retirement system effectively. The OADR is calculated by dividing the population aged 65 and over by the population aged 15-64, then multiplying by 100.

Statistics published by the World Bank Group2, an organization dedicated to creating “a world free of poverty on a livable planet,” place the U.S. OADR at 27.7, up from 21.5 a decade ago. By definition, this ratio indicates that for every 100 people of working age, there are 27.7 people over the age of 64. Mathematically, this ratio indicates that there are roughly 3.6 U.S. working-age people for each senior (100 / 27.7 = 3.61). This metric, of course, differs from the taxpayer-to-beneficiary ratio cited above, since not all those aged 15-64 are actually in the workforce. In fact, the labor force participation rate for this age group is roughly 74%, according to some sources. (It is perhaps statistical irony that 74% of the 3.61 factor equals 2.7, the most recently reported taxpayer-to-beneficiary ratio.)

The OADR, in essence, measures the trend toward greater economic and social responsibility shouldered by the working-age population and, as such, aids researchers in developing plans for the long-term sustainability of various retirement programs.

So, How Does the U.S. OADR Relate to Insolvency?

While there’s no direct correlation between OADR and Social Security financing, it’s reasonable to equate an upward trend in OADR with increased financial strain on the system’s pay-as-you-go financing structure. As the proportion of the retirement-age population continues to grow, and as the proportion of the total population — especially the taxpaying portion of the workforce — lags behind this growth, it becomes clear that program changes are needed to reshape Social Security to meet the demands of the 21st-century — and beyond — economy.

It’s a puzzle now confronting Congress, and the steadily turning calendar pages make the search for palatable solutions to Social Security’s financing problems an ever-increasing priority, certainly in the minds of current and future retirees.

[1] Mercatus Center, How Many Workers Support One Social Security Retiree?, https://www.mercatus.org/sites/default/files/worker-per-beneficiary-chart-jpeg.jpg.

[2] https://databank.worldbank.org/source/health-nutrition-and-population-statistics/Series/SP.POP.DPND.OL